Contagious Disease

Page 2 of 3

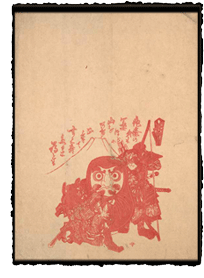

An anonymous hōsō-e in the collection

represents another interesting variation on this theme. At center is a life-sized red Daruma toy, supported on either side by

a warrior: to the left is Shōki, recognizable through his Chinese-style

costume; and on the right is the archer Tametomo. The toy, with its rounded

bottom and distinctive red-hooded head, is derived from the famous Zen

patriarch Daruma (Skt. Bodhidharma, active 6th c.). An anonymous hōsō-e in the collection

represents another interesting variation on this theme. At center is a life-sized red Daruma toy, supported on either side by

a warrior: to the left is Shōki, recognizable through his Chinese-style

costume; and on the right is the archer Tametomo. The toy, with its rounded

bottom and distinctive red-hooded head, is derived from the famous Zen

patriarch Daruma (Skt. Bodhidharma, active 6th c.).

An Indian monk who

brought the precepts of Chan (Zen) Buddhism to China, Daruma famously spent so

long in seated meditation that his legs atrophied, and his eyelids fell away —

hence the doll's unblinking gaze. That

the dolls return to their upright position after being tilted symbolizes the

qualities of determination and steadfastness, embodied in Bodhidharma's story. The combined attributes of a red robe and

watchful gaze may have led Daruma to be regarded as one who could be called

upon to protect children against smallpox.

Behind the trio in this hōsō-e is a simple linear

rendering of Mt. Fuji's conical peak. Japan's

foremost sacred mountain, Mt.

Fuji was also deemed a

protective hōsōgami. Popular

saying likened the raised form of a smallpox scab — a sign of imminent recovery

— to the mountain's characteristic shape.

A second hōsō-e depicts the hero

Kintarō as a muscular baby wearing a bib emblazoned with the first

character from his name, kin (gold). Over his shoulder he carries the

giant hatchet that accompanies him everywhere — like Hercules' club, a potent

symbol of his strength and bravery. Like

Daruma in the previous image, the boy's gaze is direct and steadfast, as he

casts a protective eye on his surroundings. A second hōsō-e depicts the hero

Kintarō as a muscular baby wearing a bib emblazoned with the first

character from his name, kin (gold). Over his shoulder he carries the

giant hatchet that accompanies him everywhere — like Hercules' club, a potent

symbol of his strength and bravery. Like

Daruma in the previous image, the boy's gaze is direct and steadfast, as he

casts a protective eye on his surroundings.

The two previous

examples were produced before 1849, when the smallpox vaccine was introduced

into Japan. Several smallpox handbills, or hikifuda, preserved in the UCSF

collection suggest how woodblock prints were used in the campaign to encourage

people to replace their folk beliefs with confidence in a scientifically proven

means of avoiding the disease.

Prints such as these

were distributed as a means of addressing recurring doubts about the vaccine's

safety. Cow-related imagery is prevalent

in the handbills as part of a response to fears that since the first vaccines

employed a strain of cowpox, people might somehow be transformed into cows if

they agreed to be vaccinated. Prints such as these

were distributed as a means of addressing recurring doubts about the vaccine's

safety. Cow-related imagery is prevalent

in the handbills as part of a response to fears that since the first vaccines

employed a strain of cowpox, people might somehow be transformed into cows if

they agreed to be vaccinated.

By the mid-Meiji period, vaccination

was widespread, by virtue of governmental decree. However, a late nineteenth-century hōsō-e suggests that despite

these efforts, earlier faith in the power of folk deities was not completely

eradicated. Dated to 1890, the

print shows a pair of figures heavily dotted with red pockmarks running from an

angry looking black demon equipped with a bow and arrow. Titled "Suppression of Smallpox" (Hōsō taiji no zu), the print

bears an inscription (in red) explaining that the artist saw a similar picture

in an old collector's home and was told that it protected against smallpox;

thinking it might help prevent an epidemic, he recreated it for his print

publisher. By the mid-Meiji period, vaccination

was widespread, by virtue of governmental decree. However, a late nineteenth-century hōsō-e suggests that despite

these efforts, earlier faith in the power of folk deities was not completely

eradicated. Dated to 1890, the

print shows a pair of figures heavily dotted with red pockmarks running from an

angry looking black demon equipped with a bow and arrow. Titled "Suppression of Smallpox" (Hōsō taiji no zu), the print

bears an inscription (in red) explaining that the artist saw a similar picture

in an old collector's home and was told that it protected against smallpox;

thinking it might help prevent an epidemic, he recreated it for his print

publisher.

In other words, "modern" Japanese knew that this sort of talisman was outdated --

a relic of the past — but might still hedge his bets by employing one of the

charms if the need arose.

Measles

Unlike the hōsō-e, the hashika-e, or measles pictures, are less

talismans or charms themselves than a kind of pictorial guide to the magical

practices most likely to lessen the symptoms of disease. One print from the collection shows a young

boy kneeling down while a Shinto priest, dressed in white, places a wooden

bucket over his head. The sacred

white horse of Ise shrine, bearing paper strips on his back stands to the

right, and the child's mother looks on from the left. In her hand is a giant holly leaf (tarayō), thought to have protective

powers. Unlike the hōsō-e, the hashika-e, or measles pictures, are less

talismans or charms themselves than a kind of pictorial guide to the magical

practices most likely to lessen the symptoms of disease. One print from the collection shows a young

boy kneeling down while a Shinto priest, dressed in white, places a wooden

bucket over his head. The sacred

white horse of Ise shrine, bearing paper strips on his back stands to the

right, and the child's mother looks on from the left. In her hand is a giant holly leaf (tarayō), thought to have protective

powers.

Behind the figures appears an image of Mt.

Fuji, again associated

with the ability to prevent or cure pox-like diseases. The accompanying text offers a tale about

measles, and a useful list of "do's and don'ts" divided into beneficial foods (kanpyo, or dried gourd, sweet potatoes,

and so on) and things to avoid (both bathing and eating soba were to be avoided for 75 days!).

|